PROCESS

JOURNAL

investigating and unlearning,

building connections through

shared conversation and exchange

building connections through

shared conversation and exchange

LADAKH // August 20, 2023

first impressions

A feeling of dissolution and deeply felt serenity. Sharp mountain peaks covered in snow and bright sunlight welcoming crisp warmth to exposed skin. A soft breeze blowing through the willow trees whose determined roots reach far into the dry earth, gathering moisture from deep below. Butterflies and bees swirling through the dye garden, now saturated with late summer purples and dotted with sunset orange-yellows. The sounds of workers building a mudbrick house across the way drifting over on the wind and from beyond the call for midday prayer. The chain of events that brought me to Ladakh began in 2019 with a project proposal for a research trip to India. My intent was to study a traditional craftsmanship techniques, specifically a mending practice called rafoogari, and apply them to the renewal of current textile waste. Over the course of many months of research into the extensive expanse of textile heritage and culture that India is known for, I developed a fascination and commitment to pursue this research, despite in the end not receiving the scholarship.

Fast forward to 2022. Post-pandemic and after a few years of working in the industry, I was again eager to pick the idea back up. In the meantime it had taken root, and my interest in the study of material culture and traditional craft had deepened to the point that it had become a foundational tenant in my work - leading to the birth of this very project. The more I learned about globalization and increasing influence of Western, consumerist culture onto far reaches of the world, the more I felt called to investigate and understand slower, more mindful and socially-harmonious forms of creation.

Ladakh was first introduced to me through the 2010 documentary, Schooling the World, which shines a light on the loss of cultural knowledge through the colonizing influence of the modern, Westernized school system. Already the first four minutes of the film are incredibly eye-opening and show the imperialist incentives of European settlers in their quest to destroy indigenous cultures and their connection to the land. Helena Norberg-Hodge, a linguist, author and activist that lived in Ladakh over a forty year span, speaks in this film and further shares her perspective of the transformation she witnessed in her book titled, Ancient Futures; Learning from Ladakh. She writes,

One of the most striking lessons that changing Ladakh has taught me is that while the tools and machines of the modern world in themselves save time, the new way of life as a whole has the effect of taking time away. As a result of development, Ladakhis in the modern sector have become part of an economic system in which people have to compete at the speed of available technologies.1

Ladakh and the local way of life is special for many reasons, but a main one is a closeness to nature and a simple way of living, that in the industrial world has evaporated from our understanding. There are still nomadic communities that exist, and through an apprenticeship with the social enterprise, we are KAL, I have the priviledge of connecting with them.

We are KAL works closely with the nomadic community, the Changpa, who inhabit the Changthang plateau, on the border between India and Tibet in high Himalayas at about 5,000m. The community used to be comprised of nearly 100 families, but has now shrunk down to only 14, living in rebo tents traditionally made of yak hair. Each family owns several hundred animals; sheep, goats and yak, that are taken up into the mountains each day by a shepherd.

A few days after arriving in Ladakh, and getting acclimated to the altitude, we drove up to spend a few days in Karnak. We packed the truck with tents, warm clothing, fresh vegetables and baked goods, and drove up into the mountains. I watched the landscape transform from the bed of the truck, as we wound through red rock mountains and along an ice blue river. The colours were breathtaking ~ bright purple wildflowers dotted red rock mountains and along the roadside wound an ice blue river. As we drove higher and higher, the greenery dissapeared and the temperature dropped. The jagged rock softened and the mountains opened into barren hillsides, as we reached the plateau.

In the fading light, we set up the tents and put on our additional layers, and then joined Angtak’s family in the rebo for a warm meal cooked over the small iron stove. Our cups were soon filled with hot butter tea as we gathered around in a circle. From far corners of the world and now together here. Outside, the stars shone brighter than I’ve ever seen.

1. Ancient Futures by Helena Norberg-Hodge, page 106. Also a documentary.

LADAKH // August 28, 2023

way of life

Early morning on the Changthang plateau. I wake up to the sound of hooves on the dry ground and unzip my tent to see a herd of yaks make their way leisurely down to the river. Despite being the warmest summer month, the air is crisp and smoke rises from the rebos dotting the stream in the valley below. I hear voices drift down from above and look to the stone structure next to my tent, to see two women on the roof, chatting and making cheese. By squeezing the clotted milk through their fingers they are creating long clusters which are then dried in the heat of the sun. It is one of the numerous ways of transforming the yak milk, which serves as a primary form of nourishment in this otherwise unfertile landscape. Without means of electricity or the ability to keep things cool, drying cheese and meat is an essential strategy.

Each day, before the first light peers over the mountain, the community is awake. The shepherds are the first to rise, taking turns gathering their flocks and heading up into the mountains. Each family has approximately 400-700 animals, who are tended to by a single herder. Watching them gracefully control such a multitude of animals is astounding. With a couple perfectly aimed rocks, they are able to direct the herd’s movements, moving them in synchronicity across the rocky landscape.

The yaks, sheep and goats provide the foundation to the way of life of the Changpa. The goats are their primary source of income, as this community is the most known for raising a rare breed of goats, which produces a fine grade of cashmere called pashmina. The sheep and yaks are kept for their personal survival - essential for everything from the food they eat, to the tents they live in, to the clothing that keeps them warm. It is the yak and sheep wool that I am there with we are Kal to purchase, and that they will then transfrom into yarn, knit items and beautifully woven carpets (more on this in the next entry).

The harmony with which the lives of humans and animals are intertwined and the ingenuity of their interrelation, is impressive. An especially clever construction are the yak hair tents, that are both waterproof and still able to let in air. These tents last many generations and are passed from down parents to children, only needing certain panels to be repaired approximately every 20-50 years. The tents are called rebos and are held up by only a couple wooden poles in the center. In the middle of the rebo is a fire that is fed by dried animal dung that is gathered and stacked outside. This both reduces waste around the camp and eliminates the need to search for (nearly impossible to find) wood. Another important task in daily life is carrying water up from the river. Much of the washing is done at the river to save the trip, but even in the heat of August, the water is ice-cold.

While the way of life on the plateau is still very connected with the traditional lifestyle, each year brings more influence from the outside world. Now, several members of the community own a vehicle, and the men often travel to nearby towns for work or various other ventures. Children are also sent away to school, some already with the young age of three. While there is a strong sense of cultural pride among the remaining members of the community, there is also the desire to enable the younger generation access to another way of life.

On the last evening I spent in Karnak, we were invited to dinner by Topdan and his daughter Lamo. She is married and has three small children, but they are going to school and living with her husband four hours away in Leh, the main city of Ladakh. Lamo wore kindness and sadness woven together and I felt a deep melancholy as I imagined the weight of her sacrifice. Her choice to remain in Karnak was not up to her alone, but was closely linked with the familial and communal responsibility of keeping their way of life alive. Her siblings had all gone off to work and study and her mother had passed, leaving her as the only one that was left to tend to her father and maintain their home.

Her children will grow up in a different reality. Under 200km away in distance but a world of difference apart. A world with white painted walls and tennis shoes and running water. They will have access to basic comforts and a more mainstream society but they will not know the warm embrace of their mother or the vastness and intimate knowledge of the land. Their life will be filled with convenience and financial gratification, but they will not grow up in connection with their culture. They won’t experience, through daily life practice, the wisdom of how to live in balance and move with the seasons.

This is not to glorify one way and criticize another, as it is undeniable that this life is incredibly hard. Yet it also holds invaluable aspects and extremely necessary teachings. Neither in rejecting tradition or single-mindedly embracing modernity, lies the best path forward. How do we move between? Preserve some parts and shift others, slowly and mindfully adopting transitions that improve the lives of children while continuing the respect and recognition of our older generations...

~

photo to the left of Tsering Yudon getting wool from her shed. August 17, 2023.

Each day, before the first light peers over the mountain, the community is awake. The shepherds are the first to rise, taking turns gathering their flocks and heading up into the mountains. Each family has approximately 400-700 animals, who are tended to by a single herder. Watching them gracefully control such a multitude of animals is astounding. With a couple perfectly aimed rocks, they are able to direct the herd’s movements, moving them in synchronicity across the rocky landscape.

The yaks, sheep and goats provide the foundation to the way of life of the Changpa. The goats are their primary source of income, as this community is the most known for raising a rare breed of goats, which produces a fine grade of cashmere called pashmina. The sheep and yaks are kept for their personal survival - essential for everything from the food they eat, to the tents they live in, to the clothing that keeps them warm. It is the yak and sheep wool that I am there with we are Kal to purchase, and that they will then transfrom into yarn, knit items and beautifully woven carpets (more on this in the next entry).

The harmony with which the lives of humans and animals are intertwined and the ingenuity of their interrelation, is impressive. An especially clever construction are the yak hair tents, that are both waterproof and still able to let in air. These tents last many generations and are passed from down parents to children, only needing certain panels to be repaired approximately every 20-50 years. The tents are called rebos and are held up by only a couple wooden poles in the center. In the middle of the rebo is a fire that is fed by dried animal dung that is gathered and stacked outside. This both reduces waste around the camp and eliminates the need to search for (nearly impossible to find) wood. Another important task in daily life is carrying water up from the river. Much of the washing is done at the river to save the trip, but even in the heat of August, the water is ice-cold.

While the way of life on the plateau is still very connected with the traditional lifestyle, each year brings more influence from the outside world. Now, several members of the community own a vehicle, and the men often travel to nearby towns for work or various other ventures. Children are also sent away to school, some already with the young age of three. While there is a strong sense of cultural pride among the remaining members of the community, there is also the desire to enable the younger generation access to another way of life.

On the last evening I spent in Karnak, we were invited to dinner by Topdan and his daughter Lamo. She is married and has three small children, but they are going to school and living with her husband four hours away in Leh, the main city of Ladakh. Lamo wore kindness and sadness woven together and I felt a deep melancholy as I imagined the weight of her sacrifice. Her choice to remain in Karnak was not up to her alone, but was closely linked with the familial and communal responsibility of keeping their way of life alive. Her siblings had all gone off to work and study and her mother had passed, leaving her as the only one that was left to tend to her father and maintain their home.

Her children will grow up in a different reality. Under 200km away in distance but a world of difference apart. A world with white painted walls and tennis shoes and running water. They will have access to basic comforts and a more mainstream society but they will not know the warm embrace of their mother or the vastness and intimate knowledge of the land. Their life will be filled with convenience and financial gratification, but they will not grow up in connection with their culture. They won’t experience, through daily life practice, the wisdom of how to live in balance and move with the seasons.

This is not to glorify one way and criticize another, as it is undeniable that this life is incredibly hard. Yet it also holds invaluable aspects and extremely necessary teachings. Neither in rejecting tradition or single-mindedly embracing modernity, lies the best path forward. How do we move between? Preserve some parts and shift others, slowly and mindfully adopting transitions that improve the lives of children while continuing the respect and recognition of our older generations...

~

photo to the left of Tsering Yudon getting wool from her shed. August 17, 2023.

LADAKH // September 10, 2023

weaving into being

Kinship and descent are for a community the ‘flow of life’; cloth can be the essential mediator. In Rupshu [a plateau and valley in southeast Ladakh], the woven cloth is soon as an expression of a family network - a medium that links men to women, and mothers to their children. These concepts are echoed through Abi Yangzom’s words... ‘Warp and weft is always there in relationships... After all, we are all warp and weft (nya-zha rgyu spun yin).’

Women’s weaving is, therefore, critical to preserving the order of the everyday world. But more than that, their weaving is also important in ensuring the continuity of the world. Beyond the womb, weaving and cloth also signify notions related to kinship and descent. 1

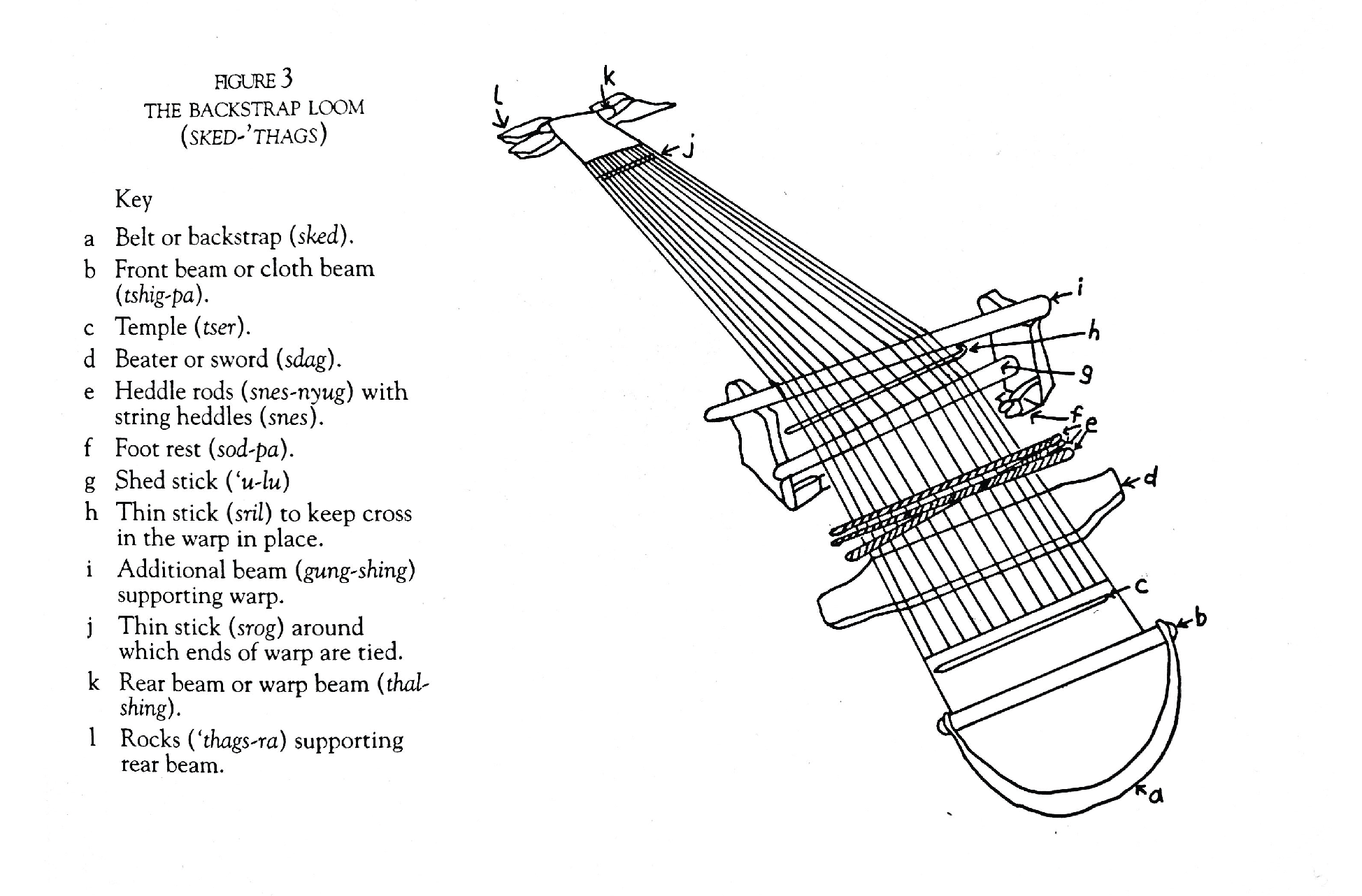

The continuity, the connection, the tension held through the body ~ from toes to fingers, and transferred into the fibers. Sitting within the embrace of the backstrap loom, which is the most common form of weaving for the women of Ladakh, one does not take long to relate to nurturing a life. It is easy to get lost in the rythmic back and forth of the weft thread, as it moves through alternating tunnels of warp, lifted with a light wooden branch. With each passage, the threads feel more familiar and the mind is freed to wander. Being quite literally bound to ones practice leaves little room for restlessness and even less for distraction, especially when a single missed thread will affect the integrity of the whole piece.

Ladakhi women would traditionally learn to weave from their mothers, usually around the ages of 15 or 16. While men learned as well, it was usually much later, between 20 and 30. Women would commonly weave on a backstrap loom, where the tension of the body holds the loom in place.

While children are increasingly sent away to be educated away from the home and are no longer learning the weaving, there are still many women in the older generation that have carried on these practices despite drastic lifestyle changes such as resettlement in the city. We are Kal works with a group of such women, providing them with a consistent income and harmonious work environment and empowering their craft by sharing their work on an international platform. The women are between 50 and 60 and all have left their previous life in the mountains to come live in the outskirts of Leh, in an area called Karnak-ling (named so because the majority of inhabitants are all from Karnak).

The women first sort the raw wool into different grades based on the quality, colour and level of dirt. Then they wash it and let it dry in the sun, at which point it is either dyed or kept its natural colour. It is then put through carding machines, to comb the fibers and ready it for spinning. The women do all of the spinning by hand, using a wooden drop spindle. This part of the process is especially difficult, as only an evenly spun thread will have the strength to hold the warp (the vertical threads, which carry most of the weight) of the loom. The below sketch, from the book Living Fabric1, illustrates the anatomy of the loom.

Backstrap loom weaving is also still practiced in central America and other parts of Asia and Africa, but is quickly being replaced with larger and more industrial looms. While these are much quicker in execution, the singularity, the slowness and the special nature of this handmade textile is not preserved.

Weaving is more than the physical creation of cloth, it is a practice that connects us to our ancestors and to ancient cultures all across the world. It is more than a machine that has now been replaced with something more efficient, but it is a method of meditation and meaning-making that is invaluable, especially in times of upheaval and disconnection. It enables a deeper understanding of the material and an active involvement in its transformation that is empowering as well as political. A central tenant in Mahatma Gandhi’s advocacy for civil rights and colonial resistance, was the revival of hand-spinning and weaving. He was quoted in 1927,

“If we have the 'khadi spirit' in us, we would surround ourselves with simplicity in every walk of life. The 'khadi spirit' means illimitable patience. For those who know anything about the production of khadi know how patiently the spinners and the weavers have to toil at their trade, and even so must we have patience while we are spinning 'the thread of Swaraj'. The 'khadi spirit' means also an equally illimitable faith. Even as the spinner toiling away at the yarn he spins by itself small enough, put in the aggregate, would be enough to clothe every human being in India, so must we have illimitable faith in truth and non-violence ultimately conquering every obstacle in our way.” 2

1. Living Fabric, Weaving among the Nomads of Ladakh Himalaya by Monisha Ahmed

2. Gandi quotes on Khadi, MK Gandhi

material inquiries

PROCESS JOURNAL // january 2023

relationality

“In a real sense all life is inter-related. All are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny. Whatever affects one directly, affects all indirectly.1”Many writings use cloth, fiber, thread - or other related terminology - to descibe relationality in various aspects of social life. The invention of clothing was a shaping moment in our evolution and since then has woven its way into our cultural identities and social structures. Clothing is a means of communication and a form of connection. It dictates how we see ourselves and how we wish to be seen by others. Our way of dress helps distinguish us and signal our values to those around. It also allows is to recognize similarities and shared interests and can provide an idea of a strangers story - all through materials, colours, shapes and details.

The culture of clothing is incredibly intricate and deeply complex. However, it is also destructive. It has been seen to promote classism and encourage materialism. On our current era’s stage of mass consumption, the production and consumption of clothing has taken a leading role. The rapid turnover and cheap price tags of ‘fast fashion’ have created an insatiable demand for newness and change, without paying a fraction of the real cost2. Quantity has replaced quality and to have has become more important than to be.

In this great acceleration, the stories behind what we wear have fallen to the back. What do our garments say about us and how can we dress in harmony with a collective vision of healing for the world? Material culture can be a powerful force to reenvision a world dictated by financial interests and billboards of photoshopped models, into into a world of authentic care and connection.

1. Martin Luther King Jr., Letter from Birmingham Jail: Martin Luther King Jr.'s Letter from Birmingham Jail and the Struggle That Changed a Nation

2. A new report launched this week by the Ellen MacArthur Foundation, via Circular. For waste and Water Professionals, claims that

“every second, the equivalent of one truck of textiles is either landfilled or burned worldwide.”

PROCESS JOURNAL // january 2023

clothing culture

A common question by people, upon hearing that I work in fashion, is to ask my opinion of their outfit. Is this fashionable? While my responses changed with the years, I would find different ways of evading the question (years of experience did not make me comfortable imposing my personal taste on someone I just met). I found other aspects of the outfit to be more relevant. Who made it? Does the fabric feel good on your skin? Do you have good pockets? Does the colour bring you joy?

The more time I spent in the ‘fashion’ environment, the less it made sense to me. Drawn in to this world through my connection to creation and craft, the exclusivity and elitism that infused the industry never spoke to me. Fashion is often seen as a space where people are either ‘in’ or ‘out’, but what does that even mean? And who decides?

The greatest takeaway that I have gathered after working in the industry is that ‘fashion’ in that sense doesn’t exist. There is no objective way to guage whether someone is in or out, because these landmarkers are subjective. Each of us develops our individual taste, informed by our interests and our occupations and the mundane functionality of what we have to do that day. For someone working with the land, clothes follow a different code than someone working at a desk, yet both are equally valuable and signficant forms of expression. Whether we choose an outfit based on function or fashion, (nearly) all of us are choosing what we put on our body, on a daily basis. Whatever our relation to it is, clothing is our first layer of home. It is our warmth and our comfort and our way of communicating something about ourselves to the outside world.

Clothing is culture, and less than fifty years ago, most of it was created locally, by hand.

... a type of small-scale textile manufacturing thrived among every group of agriculturalists across the world. In our present world... the system of production responsible for making all these clothes has everywhere become more extrac-tive, centralized, and concentrated among a few megacorporations... And what had once been the world ’s most common and widely distributed popular art—making textiles—has almost disappeared from the hands of the artisan. In the preindustrial period, anthropologists estimate, humans devoted at least as many labor hours to making cloth as they devoted to producing food. It is almost impossible to overstate how enormous was the change in the daily rhythm when textile work disappeared from everyday life and moved into the factory.1Today’s reality is a heartbreaking absurdity. The majority of clothing is mass-produced in slave-like conditions before being shipped across the world and consumed, worn and discarded - in record time. It is then reshipped around the world again as ‘second-hand’ where it piles up on the shores of a country (typically in the Global South) - sometimes even the same country whose natural recources and labor force were plundered to construct the pieces in the first place. This devastating cycle is well-documented in Dead White Man’s Clothing, a multimedia project that explores the affect of second-hand trade in Accra, Ghana.

With the loss of craft, culture is weakened. As values are increasingly dicatated by economic interests, the context of clothing is losing its importance and the conditions of its creation have been obscured. Most of garment production happens behind closed doors, thousands of miles away. Once clothing is discarded, it is whisked from view nearly just as quickly. But there is no such thing as away, and something - or someone - being out of sight does not make it lose affect.

Each article of clothing in our closet has been constructed by human hands out of resources taken from the earth we stand on. Through our interaction with these pieces, we choose to be in a certain relation to our human family and to the world. Just as the food movement has brought increased awareness to the importance of what we put in our body, the material movement is here to show that what we put on our body has just as critical of an effect.

1. from the Introduction of Worn, A People’s History of Clothing by Sofi Thanhauser

PROCESS JOURNAL // february 2023

the power of stories

Through the stories we share weave our pattern of place into the world around us. These are the threads connecting us to our outer surroundings, as well as orienting our inner realms of understanding. Our learned reality is created through the stories we receive and repeat. Many stories are presented as inarguable truth, while many others are dismissed as myth or fable. Often, ‘modern’ stories carry more legitimacy within current society. Such a story is the story of progress. Within this narrative, our salvation will be found in the continuous speeding forward. The havoc that extractive capitalism is wreaking on the planet will be solved through further technological advancement and the increased encroachment into the earth’s natural systems is seen to be integral to our development as a species. But is it?

“The situation on Earth today is too dire for us to act from habit—to reenact again and again the same kinds of solutions that brought us to our present extremity. Where does the wisdom to act in entirely new ways come from? It comes from nowhere, from the void; it comes from inaction. When we see it, we realize it was right in front of us all along. It is never far away; yet at the same time it is in a different universe—a different Story of the World.”1

Our actions and relations are motivated by our worldview, and the understanding of our roles in society. We are brought up to view ourselves as seperate individuals, in competition with those around us. Yet, if we look to our natural surroundings, we see that all of existence depends on extensive collaboration. Our separation from one another and from nature is another story that is repeated in modern society. From a perspective of scarcity, we learn to see others as competitors rather than to understand that our future survival is mutually codependent.

Cultural work, the work of infusing people’s imaginations with possibility, with the belief in a bigger future, is the essential fuel of revolutionary fire.2

As Aurora Levins Morales writes in the book, Medicine Stories, “What we need is a collective practice in which investigating and shedding privilege is seen as reclaiming connection, mending relationships broken by the system, and is framed as gain, not loss. Deciding that we are in fact accountable frees us to act. Acknowledging our ancestors’ participation in the oppression of others (and this is ultimately true of everyone), and deciding to balance the accounts on their behalf and our own, leads to less shame and more integrity, less self-righteousness and more righteousness, more humility, compassion and a sense of proportion.2”

This book - as well as Aurora’s essays on Patreon - are filled with deeply insightful and thought provoking reflections and calls to action. Her work continues to be an important source of inspiration for this project, as well as the writings of Charles Eisenstein, who was quoted at the beginning of this entry. Both investigate and celebrate the power of story as a source for societal shift towards harmonious interrelation.

The need for stories that inspire connection and interdependence is irrefutable in times of increasing alienation and dissociation. These stories can become our north stars as we strive to orient ourselves in new - yet ancient - ways. Since our ancestors could communicate, stories were used to transfer knowledge and values from one generation to another. If we shift our attention away from the stories that the current system of domination is telling us, what will rise up in that space? Perhaps we will begin to realize that to be ‘disconnected’ has more to do with distance from what makes us human rather than being ‘unplugged’ from technology.

As we make meaning of the world around us, stories help us to trace our origins of being and illuminate our ways of becoming. Theirs is the potency to guide our attention and stir our emotion, bringing us together as a collective, driven by passion and a deep love for life.

_____________________________________________________

1. The More Beautiful World Our Hearts Know is Possible by Charles Eisenstein

2. Medicine Stories: Essays for Radicals by Aurora Levins Morales

PROCESS JOURNAL // march 2023

fabric of life

san juan, guatemala

Woven into the threads that make up the garments we wear is a rich story. Typically, we do not have the privilege of knowing who made our clothing. But what if we did? What would they tell us, and how would our interaction with that piece impact their life?

The little town of San Juan la Laguna is nestled on the shores of Lake Atitlan in the heart of the Mayan region and present day Guatemala. A main pull to this part of the world was to experience firsthand the rich textile culture that is still vibrant today. Towns abound with brilliantly coloured, hand-woven fabrics, and many Guatemalan women still wear their traditional dress. San Juan, in particular, is filled with artisans and collectives. Also a common tourist destination, the streets are lined with signs inviting visitors inside for demonstrations on weaving and natural dyeing. One such studio I visited was Casa Flor Ixaco, where I had the pleasure of experiencing a presentation by Daphne, a local Mayan woman and a key member of the cooperative. Daphne walked us through the process of creation. They begin with locally and organically grown cotton - carefully cultivated over thousands of years and in four native colours - which is then harvested, carded, spun, and naturally dyed; using seeds, leaves, flowers, tree bark, and more and is then fixed to the fiber using ground bark from the banana tree. As Daphne demonstrated the dyeing process before us, it was astounding to see the brilliance of the hue, as well as its colour-fastness - achieved with so few and so organic of ingredients. The weaving process was also a wonder to witness, which is still all completed on the backstrap loom.

Daphne shared the story of the cooperatives founding, as well as the difficulties that the women and their communities have conquered and struggled with. Working in this cooperative has not only provided the women with a source of income from which they are able to nourish and support their families, it has also enabled them to continue creating in the traditional manor. By collectivizing their efforts, they are able to create more efficiently, for example by dyeing twice a year in large quantities, rather than repeating the same process multiple times in smaller batches. These women are doing the entire process by hand, and the fact that they are competing with multinational companies and highly mechanized factories makes such adjustments extremely vital. As Daphne was demonstrating the weaving process before us on the backstrap loom, a visitor from the group asked why they choose not to used mechanized looms, as these would be much faster. She responded simply,

“This is who we are. This is our culture.”

Preserving this tradition goes beyond the physical beauty and exquisite detail of the textiles. This process of creation carries stories and significance which are impossible to grasp or even to imagine. Women have been weaving in this way for hundreds of years, weaving their sorrow and their joy, their love and their heartbreak into pieces of clothing and blankets that have warmed friend and foe alike.

Whether woven by a woman like Daphne working within an empowered cooperative of women in Guatemala, or a young Bangladeshi girl working in a people-packed factory in the slums of a nearby city, each textile holds the imprints of those who brought it into existence. Here in the ‘developed’ world, where much of this process is obscured from our view, the clothes still carry these stories.

As holders and wearers of these pieces, we are in a special position to respect all that has gone into their creation and to continue their story forward. To honor those that have held the cloth before us and to preserve the materials that surround us, doing all in our power to lengthen their lifespan and conserve their value.

OF THE CLOTH //

a celebration of material culture

a celebration of material culture