LADAKH // August 20, 2023

first impressions

A feeling of dissolution and deeply felt serenity. Sharp mountain peaks covered in snow and bright sunlight welcoming crisp warmth to exposed skin. A soft breeze blowing through the willow trees whose determined roots reach far into the dry earth, gathering moisture from deep below. Butterflies and bees swirling through the dye garden, now saturated with late summer purples and dotted with sunset orange-yellows. The sounds of workers building a mudbrick house across the way drifting over on the wind and from beyond the call for midday prayer. The chain of events that brought me to Ladakh began in 2019 with a project proposal for a research trip to India. My intent was to study a traditional craftsmanship techniques, specifically a mending practice called rafoogari, and apply them to the renewal of current textile waste. Over the course of many months of research into the extensive expanse of textile heritage and culture that India is known for, I developed a fascination and commitment to pursue this research, despite in the end not receiving the scholarship.

Fast forward to 2022. Post-pandemic and after a few years of working in the industry, I was again eager to pick the idea back up. In the meantime it had taken root, and my interest in the study of material culture and traditional craft had deepened to the point that it had become a foundational tenant in my work - leading to the birth of this very project. The more I learned about globalization and increasing influence of Western, consumerist culture onto far reaches of the world, the more I felt called to investigate and understand slower, more mindful and socially-harmonious forms of creation.

Ladakh was first introduced to me through the 2010 documentary, Schooling the World, which shines a light on the loss of cultural knowledge through the colonizing influence of the modern, Westernized school system. Already the first four minutes of the film are incredibly eye-opening and show the imperialist incentives of European settlers in their quest to destroy indigenous cultures and their connection to the land. Helena Norberg-Hodge, a linguist, author and activist that lived in Ladakh over a forty year span, speaks in this film and further shares her perspective of the transformation she witnessed in her book titled, Ancient Futures; Learning from Ladakh. She writes,

One of the most striking lessons that changing Ladakh has taught me is that while the tools and machines of the modern world in themselves save time, the new way of life as a whole has the effect of taking time away. As a result of development, Ladakhis in the modern sector have become part of an economic system in which people have to compete at the speed of available technologies.1

Ladakh and the local way of life is special for many reasons, but a main one is a closeness to nature and a simple way of living, that in the industrial world has evaporated from our understanding. There are still nomadic communities that exist, and through an apprenticeship with the social enterprise, we are KAL, I have the priviledge of connecting with them.

We are KAL works closely with the nomadic community, the Changpa, who inhabit the Changthang plateau, on the border between India and Tibet in high Himalayas at about 5,000m. The community used to be comprised of nearly 100 families, but has now shrunk down to only 14, living in rebo tents traditionally made of yak hair. Each family owns several hundred animals; sheep, goats and yak, that are taken up into the mountains each day by a shepherd.

A few days after arriving in Ladakh, and getting acclimated to the altitude, we drove up to spend a few days in Karnak. We packed the truck with tents, warm clothing, fresh vegetables and baked goods, and drove up into the mountains. I watched the landscape transform from the bed of the truck, as we wound through red rock mountains and along an ice blue river. The colours were breathtaking ~ bright purple wildflowers dotted red rock mountains and along the roadside wound an ice blue river. As we drove higher and higher, the greenery dissapeared and the temperature dropped. The jagged rock softened and the mountains opened into barren hillsides, as we reached the plateau.

In the fading light, we set up the tents and put on our additional layers, and then joined Angtak’s family in the rebo for a warm meal cooked over the small iron stove. Our cups were soon filled with hot butter tea as we gathered around in a circle. From far corners of the world and now together here. Outside, the stars shone brighter than I’ve ever seen.

1. Ancient Futures by Helena Norberg-Hodge, page 106. Also a documentary.

LADAKH // August 28, 2023

way of life

Early morning on the Changthang plateau. I wake up to the sound of hooves on the dry ground and unzip my tent to see a herd of yaks make their way leisurely down to the river. Despite being the warmest summer month, the air is crisp and smoke rises from the rebos dotting the stream in the valley below. I hear voices drift down from above and look to the stone structure next to my tent, to see two women on the roof, chatting and making cheese. By squeezing the clotted milk through their fingers they are creating long clusters which are then dried in the heat of the sun. It is one of the numerous ways of transforming the yak milk, which serves as a primary form of nourishment in this otherwise unfertile landscape. Without means of electricity or the ability to keep things cool, drying cheese and meat is an essential strategy.

Each day, before the first light peers over the mountain, the community is awake. The shepherds are the first to rise, taking turns gathering their flocks and heading up into the mountains. Each family has approximately 400-700 animals, who are tended to by a single herder. Watching them gracefully control such a multitude of animals is astounding. With a couple perfectly aimed rocks, they are able to direct the herd’s movements, moving them in synchronicity across the rocky landscape.

The yaks, sheep and goats provide the foundation to the way of life of the Changpa. The goats are their primary source of income, as this community is the most known for raising a rare breed of goats, which produces a fine grade of cashmere called pashmina. The sheep and yaks are kept for their personal survival - essential for everything from the food they eat, to the tents they live in, to the clothing that keeps them warm. It is the yak and sheep wool that I am there with we are Kal to purchase, and that they will then transfrom into yarn, knit items and beautifully woven carpets (more on this in the next entry).

The harmony with which the lives of humans and animals are intertwined and the ingenuity of their interrelation, is impressive. An especially clever construction are the yak hair tents, that are both waterproof and still able to let in air. These tents last many generations and are passed from down parents to children, only needing certain panels to be repaired approximately every 20-50 years. The tents are called rebos and are held up by only a couple wooden poles in the center. In the middle of the rebo is a fire that is fed by dried animal dung that is gathered and stacked outside. This both reduces waste around the camp and eliminates the need to search for (nearly impossible to find) wood. Another important task in daily life is carrying water up from the river. Much of the washing is done at the river to save the trip, but even in the heat of August, the water is ice-cold.

While the way of life on the plateau is still very connected with the traditional lifestyle, each year brings more influence from the outside world. Now, several members of the community own a vehicle, and the men often travel to nearby towns for work or various other ventures. Children are also sent away to school, some already with the young age of three. While there is a strong sense of cultural pride among the remaining members of the community, there is also the desire to enable the younger generation access to another way of life.

On the last evening I spent in Karnak, we were invited to dinner by Topdan and his daughter Lamo. She is married and has three small children, but they are going to school and living with her husband four hours away in Leh, the main city of Ladakh. Lamo wore kindness and sadness woven together and I felt a deep melancholy as I imagined the weight of her sacrifice. Her choice to remain in Karnak was not up to her alone, but was closely linked with the familial and communal responsibility of keeping their way of life alive. Her siblings had all gone off to work and study and her mother had passed, leaving her as the only one that was left to tend to her father and maintain their home.

Her children will grow up in a different reality. Under 200km away in distance but a world of difference apart. A world with white painted walls and tennis shoes and running water. They will have access to basic comforts and a more mainstream society but they will not know the warm embrace of their mother or the vastness and intimate knowledge of the land. Their life will be filled with convenience and financial gratification, but they will not grow up in connection with their culture. They won’t experience, through daily life practice, the wisdom of how to live in balance and move with the seasons.

This is not to glorify one way and criticize another, as it is undeniable that this life is incredibly hard. Yet it also holds invaluable aspects and extremely necessary teachings. Neither in rejecting tradition or single-mindedly embracing modernity, lies the best path forward. How do we move between? Preserve some parts and shift others, slowly and mindfully adopting transitions that improve the lives of children while continuing the respect and recognition of our older generations...

~

photo to the left of Tsering Yudon getting wool from her shed. August 17, 2023.

Each day, before the first light peers over the mountain, the community is awake. The shepherds are the first to rise, taking turns gathering their flocks and heading up into the mountains. Each family has approximately 400-700 animals, who are tended to by a single herder. Watching them gracefully control such a multitude of animals is astounding. With a couple perfectly aimed rocks, they are able to direct the herd’s movements, moving them in synchronicity across the rocky landscape.

The yaks, sheep and goats provide the foundation to the way of life of the Changpa. The goats are their primary source of income, as this community is the most known for raising a rare breed of goats, which produces a fine grade of cashmere called pashmina. The sheep and yaks are kept for their personal survival - essential for everything from the food they eat, to the tents they live in, to the clothing that keeps them warm. It is the yak and sheep wool that I am there with we are Kal to purchase, and that they will then transfrom into yarn, knit items and beautifully woven carpets (more on this in the next entry).

The harmony with which the lives of humans and animals are intertwined and the ingenuity of their interrelation, is impressive. An especially clever construction are the yak hair tents, that are both waterproof and still able to let in air. These tents last many generations and are passed from down parents to children, only needing certain panels to be repaired approximately every 20-50 years. The tents are called rebos and are held up by only a couple wooden poles in the center. In the middle of the rebo is a fire that is fed by dried animal dung that is gathered and stacked outside. This both reduces waste around the camp and eliminates the need to search for (nearly impossible to find) wood. Another important task in daily life is carrying water up from the river. Much of the washing is done at the river to save the trip, but even in the heat of August, the water is ice-cold.

While the way of life on the plateau is still very connected with the traditional lifestyle, each year brings more influence from the outside world. Now, several members of the community own a vehicle, and the men often travel to nearby towns for work or various other ventures. Children are also sent away to school, some already with the young age of three. While there is a strong sense of cultural pride among the remaining members of the community, there is also the desire to enable the younger generation access to another way of life.

On the last evening I spent in Karnak, we were invited to dinner by Topdan and his daughter Lamo. She is married and has three small children, but they are going to school and living with her husband four hours away in Leh, the main city of Ladakh. Lamo wore kindness and sadness woven together and I felt a deep melancholy as I imagined the weight of her sacrifice. Her choice to remain in Karnak was not up to her alone, but was closely linked with the familial and communal responsibility of keeping their way of life alive. Her siblings had all gone off to work and study and her mother had passed, leaving her as the only one that was left to tend to her father and maintain their home.

Her children will grow up in a different reality. Under 200km away in distance but a world of difference apart. A world with white painted walls and tennis shoes and running water. They will have access to basic comforts and a more mainstream society but they will not know the warm embrace of their mother or the vastness and intimate knowledge of the land. Their life will be filled with convenience and financial gratification, but they will not grow up in connection with their culture. They won’t experience, through daily life practice, the wisdom of how to live in balance and move with the seasons.

This is not to glorify one way and criticize another, as it is undeniable that this life is incredibly hard. Yet it also holds invaluable aspects and extremely necessary teachings. Neither in rejecting tradition or single-mindedly embracing modernity, lies the best path forward. How do we move between? Preserve some parts and shift others, slowly and mindfully adopting transitions that improve the lives of children while continuing the respect and recognition of our older generations...

~

photo to the left of Tsering Yudon getting wool from her shed. August 17, 2023.

LADAKH // September 10, 2023

weaving into being

Kinship and descent are for a community the ‘flow of life’; cloth can be the essential mediator. In Rupshu [a plateau and valley in southeast Ladakh], the woven cloth is soon as an expression of a family network - a medium that links men to women, and mothers to their children. These concepts are echoed through Abi Yangzom’s words... ‘Warp and weft is always there in relationships... After all, we are all warp and weft (nya-zha rgyu spun yin).’

Women’s weaving is, therefore, critical to preserving the order of the everyday world. But more than that, their weaving is also important in ensuring the continuity of the world. Beyond the womb, weaving and cloth also signify notions related to kinship and descent. 1

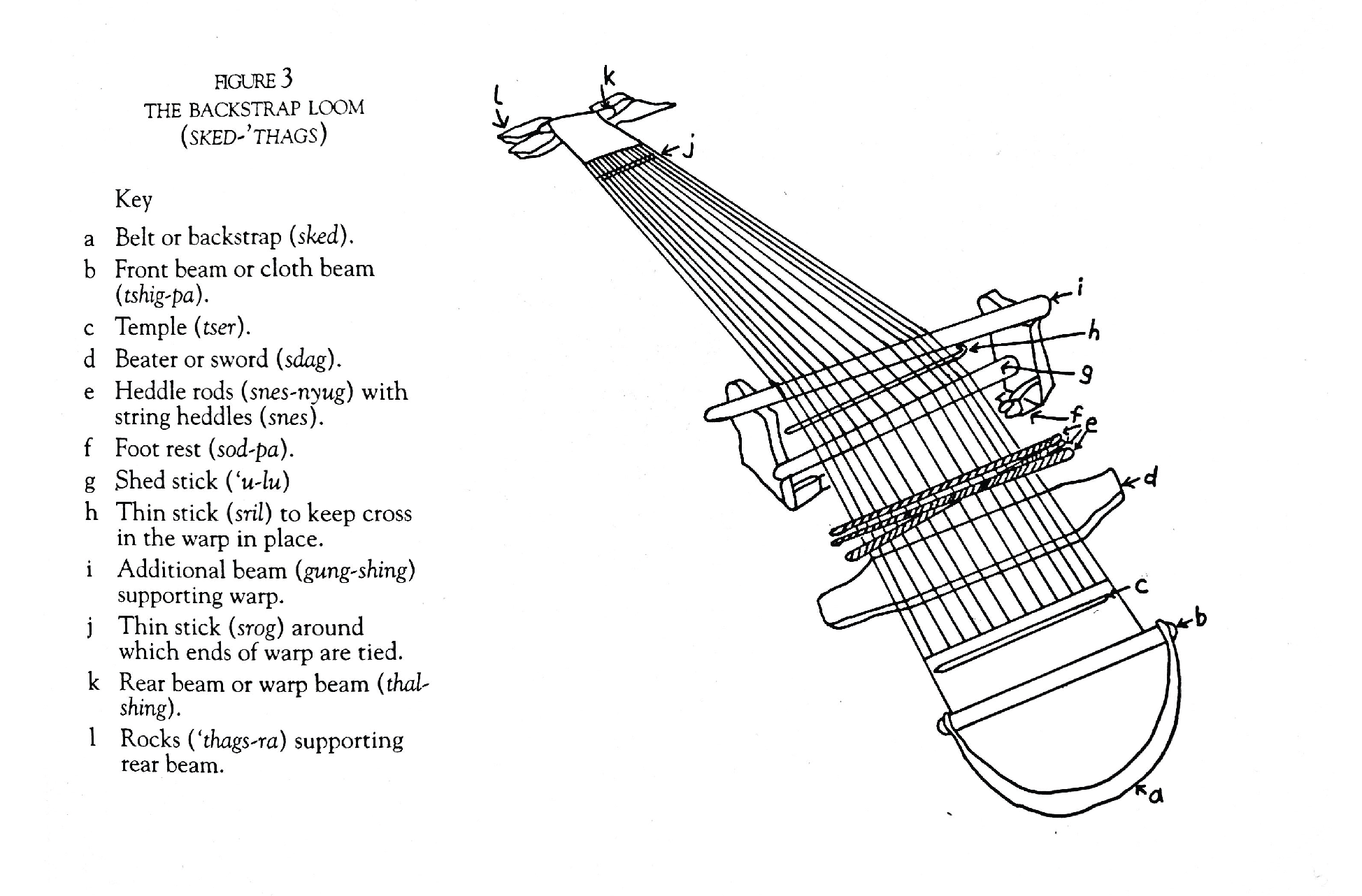

The continuity, the connection, the tension held through the body ~ from toes to fingers, and transferred into the fibers. Sitting within the embrace of the backstrap loom, which is the most common form of weaving for the women of Ladakh, one does not take long to relate to nurturing a life. It is easy to get lost in the rythmic back and forth of the weft thread, as it moves through alternating tunnels of warp, lifted with a light wooden branch. With each passage, the threads feel more familiar and the mind is freed to wander. Being quite literally bound to ones practice leaves little room for restlessness and even less for distraction, especially when a single missed thread will affect the integrity of the whole piece.

Ladakhi women would traditionally learn to weave from their mothers, usually around the ages of 15 or 16. While men learned as well, it was usually much later, between 20 and 30. Women would commonly weave on a backstrap loom, where the tension of the body holds the loom in place.

While children are increasingly sent away to be educated away from the home and are no longer learning the weaving, there are still many women in the older generation that have carried on these practices despite drastic lifestyle changes such as resettlement in the city. We are Kal works with a group of such women, providing them with a consistent income and harmonious work environment and empowering their craft by sharing their work on an international platform. The women are between 50 and 60 and all have left their previous life in the mountains to come live in the outskirts of Leh, in an area called Karnak-ling (named so because the majority of inhabitants are all from Karnak).

The women first sort the raw wool into different grades based on the quality, colour and level of dirt. Then they wash it and let it dry in the sun, at which point it is either dyed or kept its natural colour. It is then put through carding machines, to comb the fibers and ready it for spinning. The women do all of the spinning by hand, using a wooden drop spindle. This part of the process is especially difficult, as only an evenly spun thread will have the strength to hold the warp (the vertical threads, which carry most of the weight) of the loom. The below sketch, from the book Living Fabric1, illustrates the anatomy of the loom.

Backstrap loom weaving is also still practiced in central America and other parts of Asia and Africa, but is quickly being replaced with larger and more industrial looms. While these are much quicker in execution, the singularity, the slowness and the special nature of this handmade textile is not preserved.

Weaving is more than the physical creation of cloth, it is a practice that connects us to our ancestors and to ancient cultures all across the world. It is more than a machine that has now been replaced with something more efficient, but it is a method of meditation and meaning-making that is invaluable, especially in times of upheaval and disconnection. It enables a deeper understanding of the material and an active involvement in its transformation that is empowering as well as political. A central tenant in Mahatma Gandhi’s advocacy for civil rights and colonial resistance, was the revival of hand-spinning and weaving. He was quoted in 1927,

“If we have the 'khadi spirit' in us, we would surround ourselves with simplicity in every walk of life. The 'khadi spirit' means illimitable patience. For those who know anything about the production of khadi know how patiently the spinners and the weavers have to toil at their trade, and even so must we have patience while we are spinning 'the thread of Swaraj'. The 'khadi spirit' means also an equally illimitable faith. Even as the spinner toiling away at the yarn he spins by itself small enough, put in the aggregate, would be enough to clothe every human being in India, so must we have illimitable faith in truth and non-violence ultimately conquering every obstacle in our way.” 2

1. Living Fabric, Weaving among the Nomads of Ladakh Himalaya by Monisha Ahmed

2. Gandi quotes on Khadi, MK Gandhi

OF THE CLOTH //

a celebration of material culture

a celebration of material culture